To see which of the drawings are available and to purchase them please visit my shop.

The red-tailed black cockatoo: Calyptorhynchus banksia

Cockatoos are birds that fall within the Parrot order (Psittaciformes). Cockatoos are mainly found in the Australasian region of the world. The red-tailed black cockatoo is a bird found across the northern parts od Australia, preferring dry bush land to the more tropical regions. This bird is a sight to behold, with the males sporting the characteristic bright red patterns on their tail feathers, matched to the just as bright yellow striped feathers of the female, setting a stark contrast to the black of the rest of their plumage. Like other parrots, these are quite long-lived birds, (thought to live to around 25 in the wild) and form life long pair bonds within their flocks.

Considered totemic animals by many different aboriginal tribes, the redtailed black cockatoos feature in a large number of stories that go back thousands of years. However, habitat and food loss is creating a major threat to them. They are seed eaters with rather specific preferences, and a lot of their time is spent foraging. The Marri and Jarrah trees that produce the majority of the seeds that they consume are very slow growing trees, and continue to be cleared to make space for agricultural land. Currently the Western Australian subspecies is classed as endangered.

Grey crowned crane (Balearica regulorum)

The national bird of Uganda and loved from east to south Africa, this bird with the halo around its head is divided into two subspecies they occur from the DRC to eastern South Africa. There is a lot of dancing with these birds- for mating, after mating, and really just throughout the year. One fact that I found quite endearing is that their love for rhythm carries their sense of community and tradition in another way- observing populations of cranes researchers found that it is common for the courting rituals do not occur only between the two birds in question, but that at the end of the courtship the entire community will gather around the new happy couple to throw a last party before the love birds depart on their honeymoon.

Grey crowned cranes sharetheir nest building and incubation duties, but their task is not as arduous as for other bird species: their chicks are what is called precocial meaning, thatwhen they are born they are quite far in their development, they can immediately run (and dance) and will be independent quickly. On the bird continuum, precocial is contrasted with “altricial”development, as can be seen in pigeons, hummingbirds, songbirds or man others, where the young hatch as naked and blind little worms that require large amounts of care in their first weeks.

The barn owl (Tyto alba)

This is not only the most widespread owl, but one of the most widely occurring bird species overall, found on all continents except for Antarctica and in most kinds of habitat except for the polar and desert regions. They have an extremely low body weight to wing power ratio, meaning that they have incredible ease flying and especially flying slow as, unlike most other birds, they do not have to rely on the momentum of the forwards motion to create lift. Their flight is almost soundless as a consequence of this and a special adaptation in their foremost feather covered in tiny hooks to break the sound of air hitting the wing ledge.

Being mainly nocturnal they are often seen around dawn and dusk as they head out to their hunting grounds, but they have been shown to be able to hunt in almost perfect darkness by the power of sound alone. With their silent flight and their extremely sensitive ears (apparently the most sensitive of any animal ever tested), they are able to pick up on the fleeting sounds that their prey (mainly small mammals) make and locate the source of the sound using the asymmetry of their ears and way their heart-shaped disk face funnels the miniscule noise.

They will usually form life long pairs that nest together during breeding (which is an annual to biannual event) but maintain separate holiday homes for the remainder of the time. Much of the daily life of barn owls has been discovered through the rise of “bird cams”, nest boxes that come equipped with cameras that let scientists ( and anyone on the internet who is interested) observe owl pairs and their hatchlings 24/7.

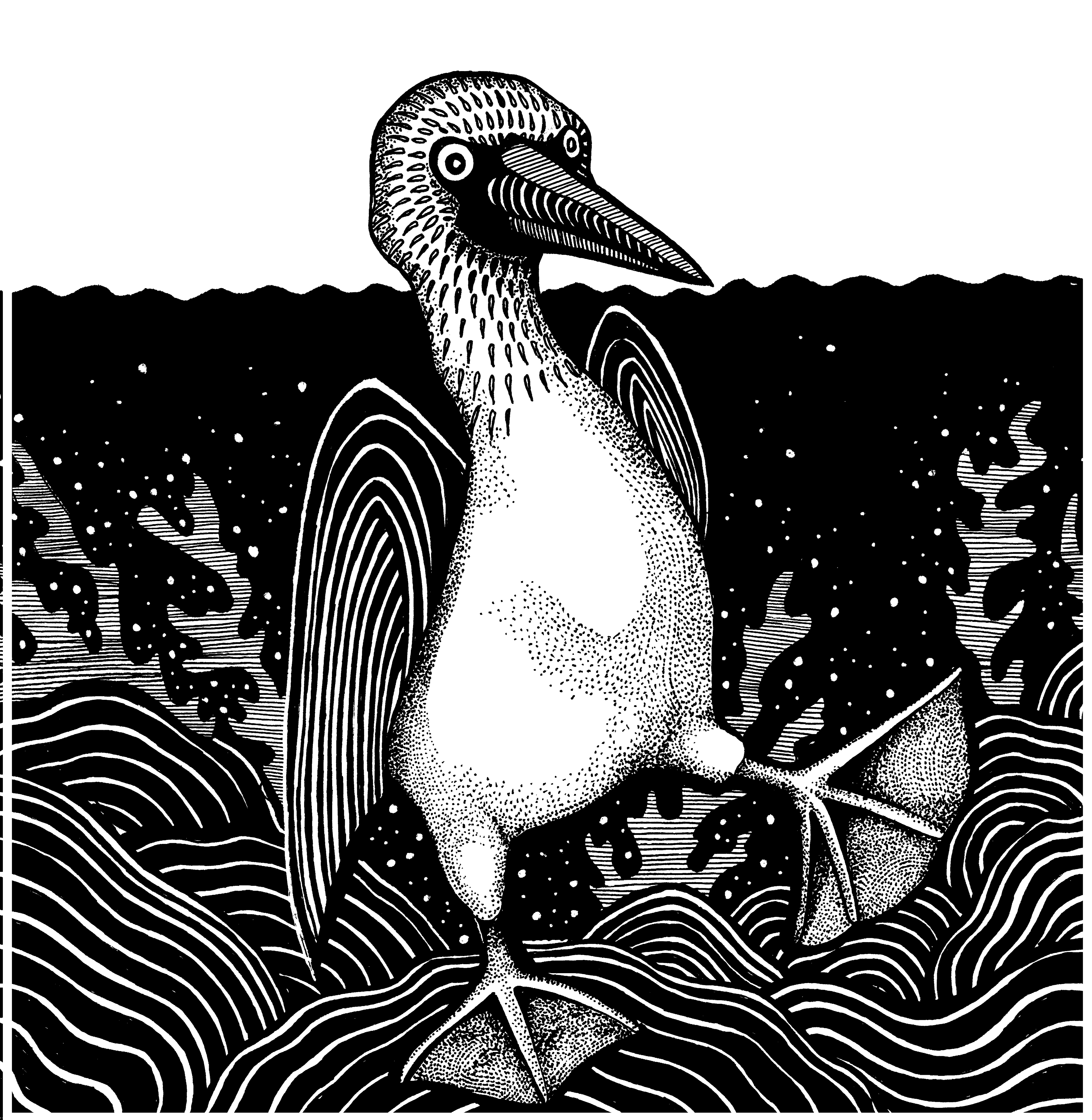

Blue footed Booby (Sula nebouxii)

This is only one of six booby species, but by far the most eye-catching with feet whose blue colour seems almost unnatural (another instance where I can believe I am doing this challenge on birds in black and white ?!). The startling colour in their feet is derived from certain carotenoids that are contained in their fishy diet, and is an incredibly important status symbols within booby social circles. Brightness and intensity of color seems to be in direct correlation to health and indicate good genes, as boobies deprived of food for only 48 hours showed fading in the coloration of their feet. As such immediate and responsive outwards sign of a bird’s health it is no wonder that the feet play a big role in mate selection rituals, as the males will parade in front of the female showing their glorious paddles from all sides. In this case however it appears that it is not only the females seizing up the males attributes as in a lot of other birds, but rather a mutual appraisal, as it has been shown that a male who lands a female with dull feet will invest less care and time in their mutual eggs than one who got a bright blue foxy lady.

Their slightly awkward demeanour on land and clownish feet have garnered them the name booby, derived from the Spanish “bobo” for “stupid”. If you see them in the air or in the water however that name appears more and more misplaced- they hunt solo,or in groups up to 12 birds , circling above the water until they lock their binocular vision on a prey beneath the surface and then dart down vertically from heights of 100 metres, reaching a speed of up to 97 kmh by the time they hit the water. Changing from one element to the other seamlessly they can then go on to pursue their prey to depths of 25 metres.

The common cuckoo: (Cuculus canorus)

The story of brood parasitism is fascinating however, and the deception reaches into the genes. Adult common cuckoos exhibit different “morphs” meaning that they can differ quite substantially in their appearance, with some taking on the appearance of sparrow hawks to frighten other birds away from their nests in order to give the female the 10 second gap that she requires to chuck one of the eggs out of the nest and lay her egg in its stead. Being obligatory brood parasites, cuckoos lay up to 50 eggs into different nests during one brooding season. Female cuckoos fall into different “gentes” or groups, each being specialized in producing eggs that closely mimick a certain host to avoid them detecting the outlier. It is thought that the gene for producing eggs of a certain look is passed from female to female, and is chromosome linked.

If undetected, cuckoos will generally hatch a few days before their adopted siblings, and, still naked and blind, instinctively begin to heave as many other eggs out of the nest as possible. As they generally grow quite a bit larger than their adoptive parents, they have to ensure substantially more food than the parents would normally suppy to one of their own. They achieve this through both auditory mechanisms, a lot more pathetic and urgent than a normal chicks, and through colours in their mouth (their “gape”) which have been shown to have almost hypnotic effects on the adoptive parents.

Nature is red in tooth and claw, and cuckoos (and apparently some other birds as well) have adapted to be the perfect exploiters. It is a remarkably effective strategy and as much as the trickery might offend our sense of ethic, the cuckoo is laughing all the way to the bank.

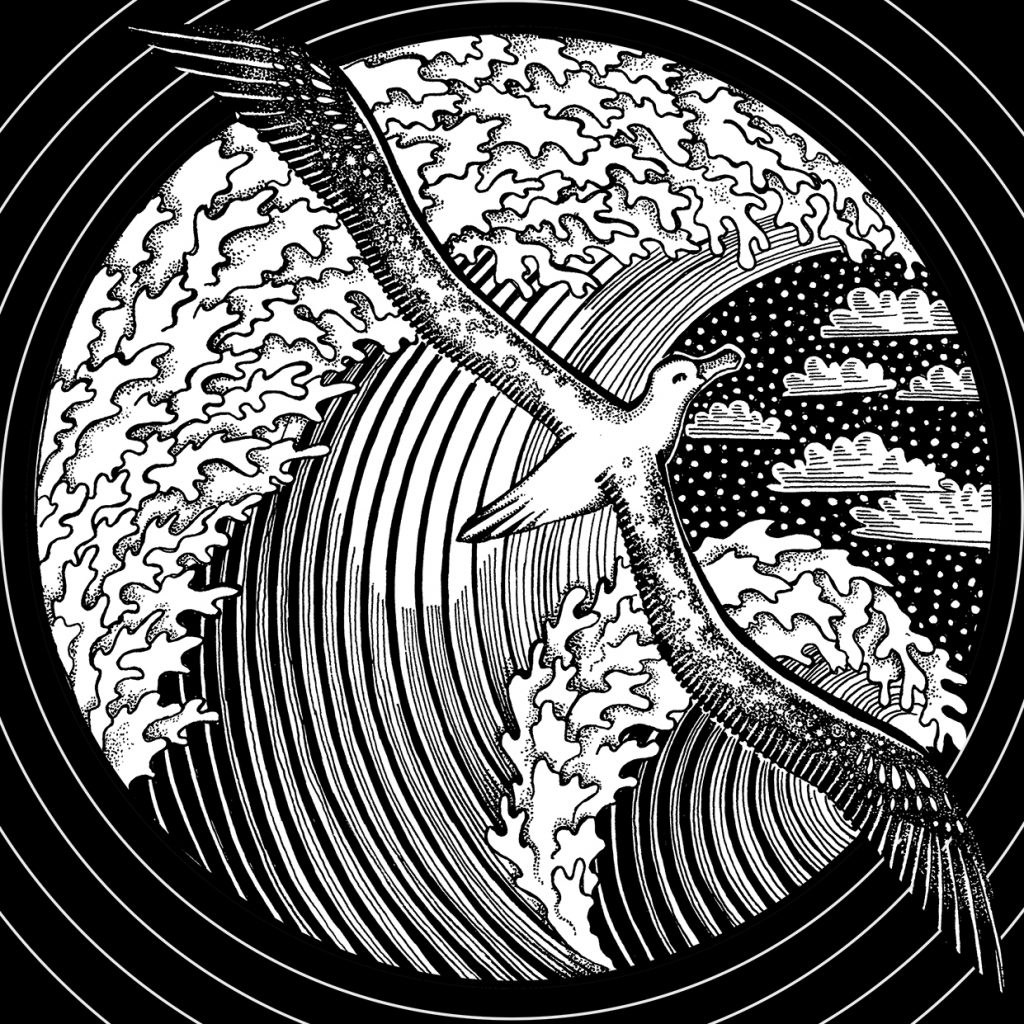

Wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans)

The bird with the largest wingspan, reaching more than 3 meters, wandering albatrosses undertake long voyages across the oceans, with single birds having been tracked to circumnavigate the southern seas in only 42 days, and performing this feat many times a year, profiting from up-winds between wave crests and troughs to propel them at speeds up to 120 kmh. Since their gliding mode of flying relies on winds and air movement, research has shown that their heart rate is not raised significantly when flying versus when resting as they are doing little in the way of flapping and have an additional mechanisms in their shoulder that allows them to “lock in” their wing once expanded, thus avoiding strain of keeping the wings erect. This, together with the ability of retiring part of their brain to a sleep like state while flying allows them to cover extremely long distances without tiring. It has been estimated that the wandering albatross spends 95% of its life in the air. There is no other bird that lives in such constant separation from all earthly things.

The solitude of this mode of life is contrasted by the other trait eternally connected with the albatross- that of devoted and enduring love. Albatrosses will form a bond with another bird over the duration of a 3 year courtship and henceforth return to the same colony in intervals to breed with only this partner over their life that can reach more than 60 years. We are not sure how the partners sync up their return home. If there is majesty, poetry and sublimity among the birds it is here.

The dodo: Raphus cucullatuus (or Dudus ineptus by Linnaeus)

So for #Inktober this year I wanted to get my head out of the water for a bit and into the air (or in some cases, like this one, on to solid ground). Welcome to #Ornithober.

I am starting with the dodo, because in a way he is the beginning – of the end. The only specimen left with live tissue, the oxford dodo, has a pathetic story to match his entire species. After being stuffed and being passed through some hands and some curators- mistakenly or otherwise- an assistant burned all of the specimen bar the beak and a foot. What a way of adding insult to injury. These birds were examples of secondarily acquired flightlessness. It appears to be a common theme among birds that if the colonization of an island succeeds (in this case Mauritius), and if this island is secluded and plentiful, then by the economy of evolutionary frugality birds will often lose their ability to fly as they do not need it anymore to forage, as there I plenty, and not to escape predators, as there are none. Until the sailors came.

But hope, also, is a thing with feathers. I hope that we will learn. Even if the story of the Dodo occurred at a time when “Conservation” was barely a word, we haven’t progressed too much in the years since, and his fate has repeated over and over again. As we go through 31 birds (that are still with us) this month, please keep in mind the Dodo and all those others that are going, going, gone.

The emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri)

Emperor penguins are extraordinary on two accounts: they are the largest penguin species, reaching up to a metre when standing erect, and they are born in the midst of the cold and dark Antarctic winter.

In order to breed under these conditions, the colony aggregates in breeding sites, often more than 200 kms from the sea where the food is. Over the duration of courtship, couples will form, and pair specific vocalisations are established to make sure that upon separation they will be able to find each other again. Once the one and only precious egg is laid, the female will transfer it very carefully to the male’s brood pouch, and for the next two months he will do nothing but keep it warm against the freezing temperatures, while fasting and waiting for the female’s return. In this time, the females travel the long distance to the sea to restock the reserves used up for the laying of the egg. Emperor Penguins are formidable swimmers, being able to stay under the water for up to 27 minutes while hunting for fish and squid (mainly). Once she has feasted, she will make the long trek back to the colony after an absence of around 2 months, where the chicks have hatched by now, and allow her starving partner to take his turn in getting some time off baby-duty and feeding after the long fast in the bitter cold.

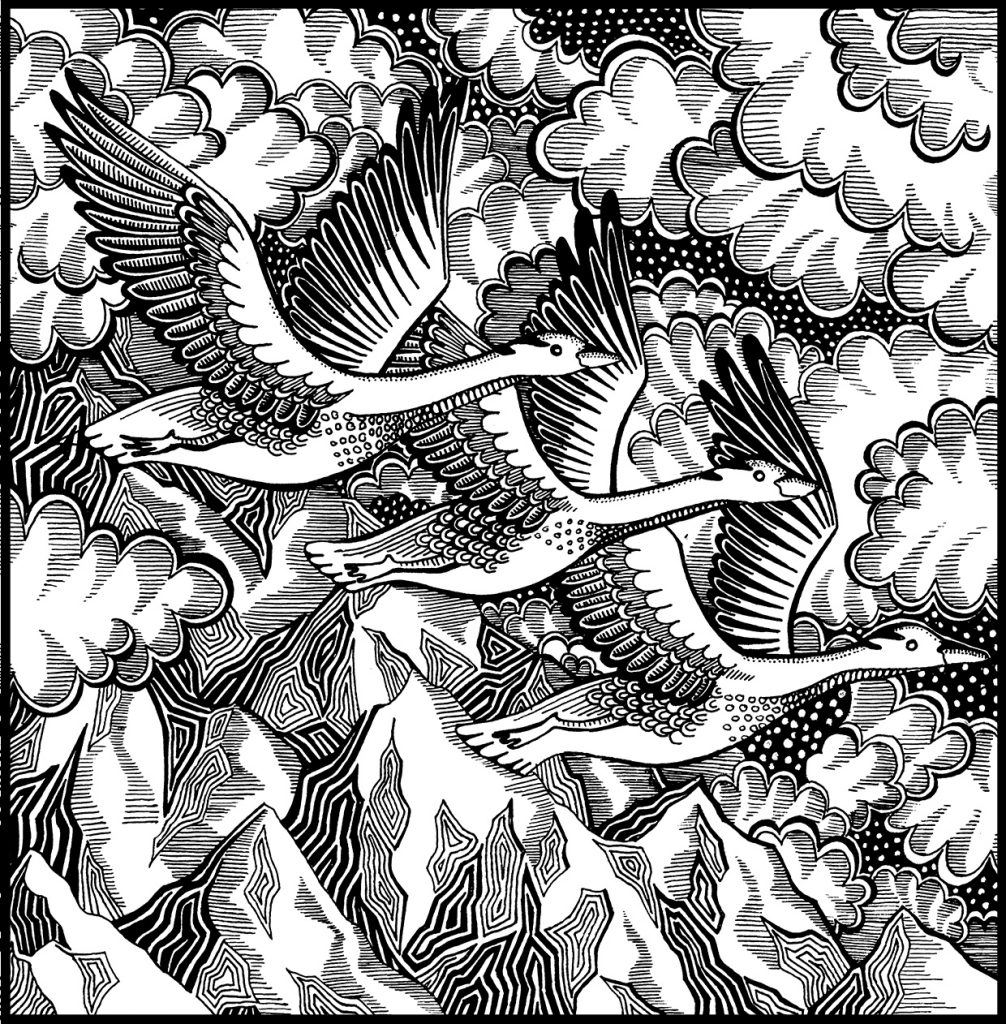

Bar-headed geese (Anser indicus)

Bar headed geese are the birds with the highest recorded flight in the world. Their summer migration takes them south, across the Himalayas from Mongolia to the northern parts of India. Bar headed geese have been recorded to generally reach 5000-6000 m altitude during this part of their migration, although individual birds have been recorded to fly as high as 8000 m above sea level. There are many hurdles to this incredible feat- flying is exhausting, the air contains one third to half of the oxygen that it does at sea level, plus the air density is lower, so you have to flap your wings EVEN harder and then there are the freezing temperatures that require increased metabolism just to keep warm.

.

While birds in general have quite a different physiology to mammals to sustain the extreme metabolism required for powered flight, including a different system for the lungs to increase gas exchange and withstand hypoxia better ( by having a “cross current” gas exchange rather than the alveolar exchange of mammals), around 50% larger hearts (proportionally) and higher capacity for oxygen distribution throughout the tissues, bar headed geese have perfected their tolerance to hypoxia allowing them this superhero like feat.

Lesser Flamingo (Phoeniconaias minor)

The lesser flamingo occurs across different parts of Africa, but one of the largest congregations is found at lake Natron in Tanzania. The high salinity and alkalinity of the waterbody means that there has historically been little competition on the lesser flamingo, plus the high salinity means that there are more Spirulina cyanobacteria that the flamingos can filter out of the water with their enormous beaks. They are perfectly adapted to this highly hostile environment with tough skin on their legs to avoid damage from the toxic water and the ability to drink water near boiling point without sustaining injuries. In recent years there have been Moves to construct “soda ash” factories along lake Natron, which would strongly disturb the particular inhostility that the flamingos are so perfectly adapted to.

The tawny frogmouth (Podargus strigoides)

This real life muppet, the Australia based tawny frogmouth is to his compatriotic paradise birds what the moth is to the butterfly. Nocturnal, they spend most of their day sleeping horizontaly on branches that their plumage lets them blend into perfectly. They are masters of camouflage and mimicry, with their feathers ressembling the mottled grey and brown of the tree barks and one of their past times in the day is an activity known as “ stumping” (not to be confused with the 2010s trend “ planking” ) where they stretch out their little head, make their body stiff and effectively evade predators by appearing as part of the tree.

Although they superficially resemble owls, these similarities are not due to any close evolutionary relationship between the two, but rather due to their shared boreal and nocturnal lifestyle. Unlike owls frogmouths are weak flyers, and have pitiful claws as they rather hunt by using their mouth to scoop up prey or alternatively by pretending that their mouth is a large yellow flower and letting insects deliver themselves, better than ubereats ever could. Since part of their range is in tropical Australia and part in the very temperate south, down to Tasmania, they have adaptations for both the freezing cold, where they can go into “torpor” a kind of temporary hibernation to preserve energy, while also having cooling mechanisms achieved through evaporation of mucus from their wide beak.

Although they look like the grouchiest of grouches, they are very sweet and affectionate with their partners maintaining strong bonds over decades through mutual preening and bringing of gifts and vocalise their love through purring sounds.

The common starling (Sturnus vulgaris)

I don’t think there is anything in the animal kingdom as mesmerizing and enchanting as the murmurations of hundreds of thousands of migrating starlings gracing the skies at dusk. The swooping, swooning, scooping movements, the contracting and expanding can make you think god himself is pulling the strings on this visual symphony.

As technology has progressed scientists have started searching for an answer that might be more of this world. Physicists and mathematicians have tried to come up with models that could shed more light on the laws governing the seeming “out of the blue” formations. In fact the closest statistical fit was found in the physics of magnetism, and the way the electrons of a particle will influence those around it as metal becomes magnetized. In starlings- it appears- the magic number is 7. That is how any birds one bird influences directly. And so, the change in direction performed by one bird- in reaction to some external stimuli, such as a predator or environmental conditions- will trickle through the entire murmuration, 7 birds at a time.

The European herring gull (Larus argentatus)

If you want to see anarchy in the animal kingdom look no further than the gulls- these glorious punks with wings. They are one of the birds that have most successfully adapted to the main global disturbance of marine habitats- people. Scavenging, stealing and bothering are what these birds are good at, and they ll show you! The fact is, that with coastal urbanization, they don’t have much of a choice. As they are growing more and more dependent on scavenging human food gulls are found further and further inland, as their habitat no longer is tied to the marine invertebrate foodsources that they depended on once upon a time.

However beyond the cacophonous screeches and aggressive assaults on anything and anyone, herring gull societies are actually very complex. One of the first big studies on bird societal structures was conducted on a colony of herring gulls in 1947 by dutch researcher Tinbergen. The complexity of gull communication and intersocietal behavior has since been studied extensively and it turns out that their vocalisations are extremely diverse and can communicate very nuanced and specific concepts. Sea gull couples, for example (they are monogamous birds) can spend weeks arguing over where to build their nest, with one partner placing a stick on the ground and conveying in body language and sound that this is the piece of land where their chicks should hatch. This will then be debated in a civilized fashion, and if no agreement can be found, the stick will be placed again and the argument begins again.

The Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica)

Today is my birthday and I wanted to celebrate it with one of my favourite birds- the atlantic puffin!

The puffin is one of those birds that are perfectly at home in the air, the water and on land, master of the elements. Their endearing clown like face undergoes a massive annual change: after the breeding season the birds “lose” their triangular eye ornaments and the bright orange plates on the beak in a partial mould before they head out to sea for winter, like someone taking off their makeup after a long party.

We know little about what they do in their solitary time at sea, but in those winter Months it appears they spend their lives on and below the waves. They are incredible swimmers, using their stout wings to “fly” underwater and their webbed feet to power the dives which can be up to around 60 meters deep.

When they return to their nesting colony they reunite with their long term mate and get down to the business of creating the next generation of puffins. Puffin “nests” are burrows, laboriously excavated by the parents and renovated each year upon their return. Puffin mothers lay a single egg, and incubation and parental duties are divided equally among the parents.

The atlantic puffin has long been hunted in Iceland, it’s meat being a traditional dish, and the hunt itself a long practiced sport, where the birds are caught midair upon their return from the cliffs into the sea in a practice called “sky fishing”. Declining numbers have however given rise to concern, and conservation efforts are now trying to reign in the hunt of these gorgeus creatures.

Bower birds (family: Ptilonorhynchidae)

If there is culture as such to be observed in the animal kingdom, apart from the primates, it is with these exquisite birds. Found in the Austro-Papuan region, bowerbirds exhibit architectural and artistic prowess to rival Michel Angelo.

In this species the female reigns supreme, and males have to work exceptionally hard to get their attention and a chance to mate. In order to impress passing females, bower birds design very specific and elaborate structures (the ”bowers”) which are then decorated with different coloured objects and sometimes even graced with especially planted gardens of specific plants or fungi. My favourite is an optical illusion, that so as to make the bower appear larger, the birds play with perspective, placing larger stones towards the end and smaller towards the front, making them all appear the same size. Traditions of the specific design and structure are imparted to younger males by “mentors”.

Making claims regarding culture in the animal kingdom is difficult, but studies to that aim have defined the following requirements for behavious to be considered “culture”: the behavior should be learned, socially taught, the behavior should be normative, and lastly, the behaviour should be collective. It appears that bower birds tick all of these boxes.

Genus Pelicaniformes (Pelicans)

Pelicans are fantastic birds, with their huge, characteristic throat pouches. There are a total of eight Pelican species within this genus, spread over all continents except for Antactica. The great white pelican is (right after the wandering albatross) the bird with the largest wingspan reaching more than 3 metres across (3 METRES!!).

Many cultures, including ancient civilizations like the Egyptians or Incas, elevated pelicans to god -like statuses. There must be something about them. In the Christian tradition and imagery one particular image, that of the mother pelican tearing skin of her own breast to feed her young in times of drought was seized upon as the ultimate symbol of christlike selfless sacrifice. This legend is believed to have arisen in a Bestiarium by Physiogorus, but appears too be quite a bit of a misunderstanding on the ancient observer’s parts, as it is thought that rather than pulling out her own skin, the mother was rather squashing fish in her pouch against her chest before feeding it to her young, and spilling some of their blood in the process. A bit less mythical a bit more practical.

The southern Cassowary (Casuarius casuarius johnsonii)

While there are three species of cassowaries this is the only one that graces Australia (in the far north) with its presence. Looking at a cassowary it is easy to see the intertwined link between the dinosaurs and “Aves”, the birds. From their enormous scaly toes to the formidable like extension on their head they seem like they just stepped out of the Jurassic age. Along with the other ratites (ostriches, emus, rheas and kiwis) they did split from all other living birds first in evolutionary terms, the split going back to around 90- 70 million years ago (long before the dinosaurs went extinct). After the ostrich, cassowaries are the heaviest birds, with females weighing around 70 and males around 40 kgs. While they do not appear very tall, due to their more hunched over posture, you do not want to cross a cassowary in the wrong way. Especially when protecting their kids, males can be extremely defensive and are known to send anyone who provokes them to the hospital with a single well placed kick with their sharp claws.

They spend most of their time solitarily and will only meet up annually or biannually to breed. Unlike many other birds, no pair bonds are formed, and the mother will leave as soon as she has laid the conspicuously green colored eggs. From here on, the father will be the sole caretaker, incubating the eggs for around 50 days, and then single-dadding it for another 9 months to make sure they grow into well-adjusted and independent cassowaries in their own right.

The southern cassowary is classed as endangered, as much of their previous habitat is lost and their numbers have further been much reduced due road traffic and introduced predators such as dogs and wild pigs.

Yellow billed Tucan (Tockus deckeni)

These birds will form monogamous pairs and nest in tree or rock cavities, sometimes taking over abandoned sites from other birds. When she is ready to lay her eggs she begins sealing the entrance to the nest with mud, fruit bits and other diverse paraphernalia until the entrance is just large enough for her to slip through. Once inside she continues her task, allowing only space for her beak to be ‘handed’ provisions my her mate while she incubates the eggs. When the chicks get too big, she breaks out, reseals the hole and helps her mate feed the kids. This species is extraordinary in another way- it forms a highly unusual and incredibly adorable mutual relationship with the dwarf mongoose found in its range in east Africa. This companionship is formed as a result of the birds and mongooses having a very similar range of food and a similar range of predators. The hornbill’s will wait above the ant mound where the mongoose are sleeping and sometimes wake them up with their call. When everyone is ready they go out foraging together, guarding each other alternately and letting out calls when a predator is sighted. The best thing about this that it has been found that the hornbills will not only call out when they see a common predator, but have a special call also for predators who only go for their mongoose friends.

Pigeon (Columba livia domestica)

Pigeons are the world’s oldest domesticated birds, with signs of human cohabitation with these marvelous animals going back to Mesopotamic plates. Pigeons have fought wars together with humans, they are amazing navigators and there is an entire industry concocting races between the finest and leanest specimens. After milleniums of being kept by humans, a large feral pigeon population has established itself in cities across the world, often considered a nuisance for defecating on statues of important generals and having adapted a kind of arrogant stance towards their human co-habitors of urban spaces. Its come to the point where large programs are dedicated to exterminating these metropolitan pigeons, wether it is through culling or massive sterilization efforts. I for one wouldnt like to imagine cities without them. They are fascinating to watch and are highly intelligent- beyond their navigational skills, they have been found to have exquisite (and discerning) taste in classical music (check out Porter and Neuringer 1984), can remember letters from the alphabet and are overall fantastic little creatures.

The sword-billed hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera)

Humming birds are only found in the America’s. While they are often confused with Sunbirds (found in areas of Eurasia and Africa) as both feed on nectar and have similar morphologies, the two only resemble each other due to convergent evolution (independently similarly evolved traits). Hummingbirds are the smallest birds with the female bee hummingbird weighing a mere 2.6 grams. Their small size means that their metabolic rate is extremely high, with more than 1000 heart beats per minute not being uncommon.

One amazing thing about hummingbirds is their coevolution with the plants that they feed on- as the primary pollinators of certain ornitophil plants the plants and birds have evolved to be perfect fits for each other- beak length matching flower size and flowers presenting themselves in the most attractive colours and providing nectar high in sucrose.

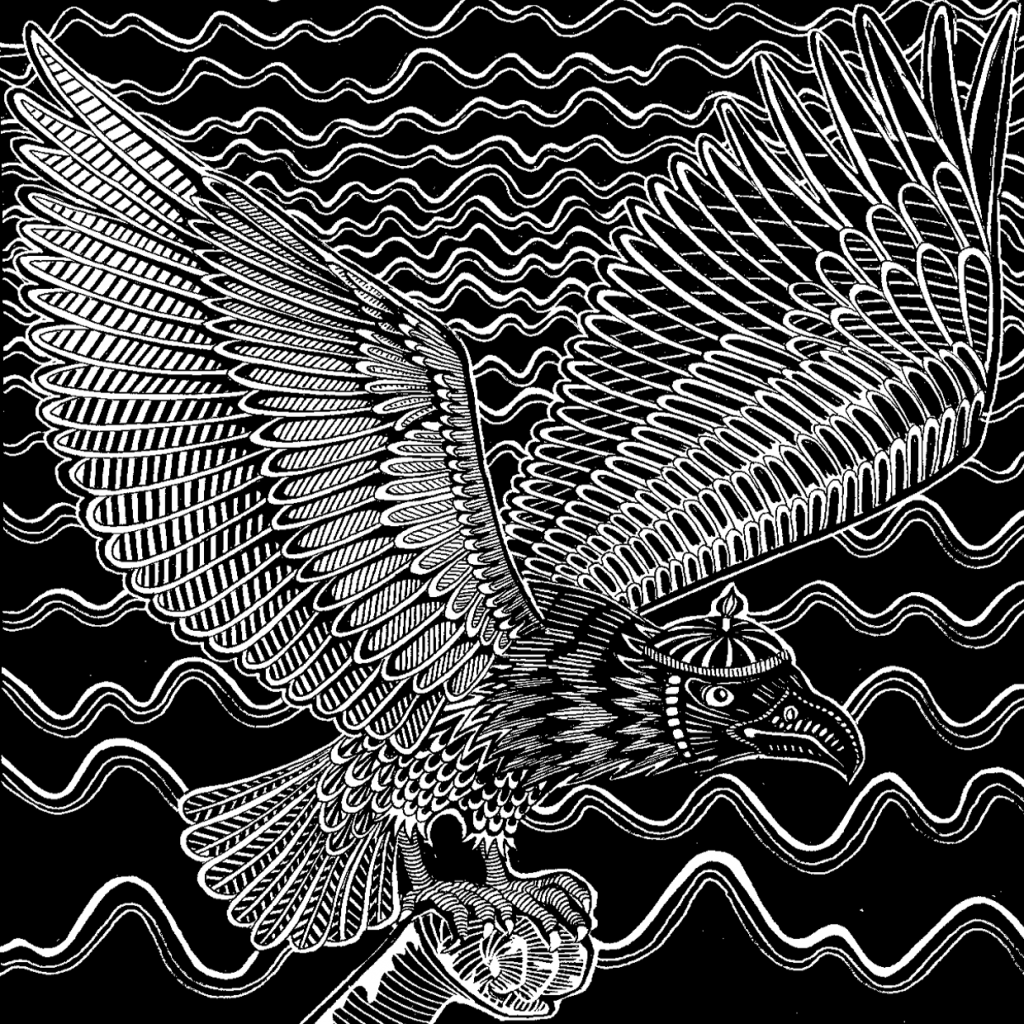

The andean Condor (Vultur gryphus)

The andean Condor is a new world vulture of truly awe inspiring size. With a wing span of more than 3 metres, it is the largest flying land bird in the world. Occurring along the western side of South America, across many latitudes, the andean Condor is an important symbol in many indigenous cultures. The Incas, for example, built Machu Pichu in the shape of a Condor, who was seen as a manifestation of the God of the sky. It remains the national bird and a national symbol of many South American countries.

Unusually, for raptor birds, the male andean Condor is larger than the female, and the sexes differ in plumage (males have a white color and some white feathers in their wings, eye color and head morphology. When courting, the male is able to change the color of his neck from red to yellow, a party trick that has been shown to have quite the effect on the ladies when executed well.

Like other vultures, the andean Condor feeds primarily on recently deceased carcasses, which he locates during his long and soaring flights over the andean mountains. As they are extremely long lived (one individual in captivity living until 79 years old), lay one egg at a time, and take care of their young for up to two years, their population is sentive to disturbances. Hunting of these birds, habitat destruction, and changes to their food populations mean that its population has been decreasing rapidly.

The common Loon (Gavia immer)

This bird’s haunting and iconic call can be heard in many American movies, generally to establish an air of wilderness and forlornness. While they look like ducks, the genus Gavia (the only genus in its order) is far removed from the ducks in evolutionary terms. These birds change between mainly inland freshwater bodies in the north American summer (for breeding) to the more coastal areas of the states, Canada and Alaska and some western European countries (known as the “nearctic” bioregion.

Feeding mainly on fish, loons are great divers, as a consequence of which, their feet, like is the case for many water birds, are found very far at the back of their body, making moving around on land difficult.

The checkered plumage depicted here is only their mating and breeding summer outfit, as they molt into a more modest grey black ensemble for winter. Breeding around the great lakes of north America, they are fierce protectors of their young, known to attack eagles and other predatory birds if they venture too close to their babies.

Due to their long stay in freshwater bodies, concerns are growing in regards to their ecological future, as disturbances to their nesting sites and poisoning of the water through run off and biomagnification of trace elements are on the rise. A group known as the “Loon rangers” has been mobilizing to preserve and protect these iconic and beautiful birds.

The Tern (Sterna hirundo)

The sea swallow is one of the farthest migrating birds, with a yearly round trip distance of 35 000 kilometres, stretching almost from arctic regions to the warm coastal waters of southern Africa an south America. Different subspecies of the common tern are found in a circumpolar distribution around the arctic circle during summer, from where they cross many latitudes to enjoy some sun in the winter months.

They have an astounding sense of location, as it has been shown that when, during an experiment researchers have “hid” a tern’s nest and eggs under a layer of sand amidst a colony of around 2000 birds, the terns will instinctively and immediately locate the place where their nest used to be and dig it back up. This is probably a adaptive mechanism to their windy and unsettled breeding grounds.

Tern colonies display another interesting characteristic: at random times the colony will rise into the air, and flap around making lots of noise for a bit, before settling back down and behaving like nothing happened. This behaviour known as “ the dread” has been puzzling researchers for years, since it is unclear what exactly might trigger it.

Indian Peafowl (Pavo cristatus)

The male peacock, with his breathtaking bouquet of a tail is a tale of its own. The uselessness of the feather extravaganza in any real way, in addition to the intricate beauty and design of it have made the male peacock the posterchild for theories on the workings of sexual selection.

The two main camps in this regard are the “run away” theory and the “handicap” theory. The “run-away” theory postulates that at some time the female peacocks might have developed a slight fancy for a somewhat longer tale in mates. This can be thought of as a trend and “just because” , or there might have been an underlying reason for this in the particular time and place. The increased success experienced by males with slightly longer tails, would have meant that their offspring also would have had genes for longer tales, while the daughters would have had genes for preferring males with longer tales. This then, over thousands of generations, would have created a force that became increasingly impractical but genetically difficult to stop.

The handicap theory on the other hand suggests that males show off some sort of visible attribute that should make life harder for them, and thus demonstrate their superiority to other males in that DESPITE the handicap they survived and thrived. This is only possible to a certain point since, as soon as the acquired handicap affects their survival in a way, this could compromise their survival before they are able to reproduce and therefore mean that those exaggerated genes, along with the poor soul who inherited them, would die out before they could sow their wild seeds and so beauty would remain in the precarious balance between life and death.

The snow petrel (Pagodroma nivea)

White like a little snowflake, the snow petrel is one of only three species (together with the Antarctic petrel and the polar Skua) that have been sighted at the geographic south pole and that breed exclusively in Antarctica, with the snow petrel having the southernmost colonies.

Their courtship is an astounding display of aerial ballet, whereby the female will challenge the male to follow her flying manouvers, soaring and falling, darting towards rock cliffs before averting collision by a last second turn of direction. When a male thus proves that he is worth his salt, the couple will find a place for their nest on the cliffs, as protected from the chilling wind as possible.

One of the main threats to their chicks are the polar skuas, who will readily devour them if left unprotected. One of the lines of defense for the snow petrel is a oily concoction that they manufacture in their stomachs and that they use as a kind of vomit projectile. The oily and acidic nature of this concoction can damage the insulating properties of the aggressors feather coat and thus expose him to the freezing Antarctic temperatures.

Petrels are named after Petrus, the apostle who following Jesus, walked on water. Petrels have acquired this saintly skill in order to facilitate their take off and landing on a calm sea, splashing about with their webbed feet.

The Hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin)

A truly dinosaur-like bird found in the amazon jungle. Genetic research conducted in 2015 found that this bird (the only extant species in its order) branched of from its fellow birds 64 million years ago, only a little while after the mass extinction at that killed the dinosaurs. They are the only living bird that have claws on their wings, a trait seen in fossils of archaeopteryx, the famous extinct flying dinosaur-bird, but in hoatzins these claws are a juvenile trait that is lost as the bird matures. Some other birds have also been found to have vestigial claws on their wings, including chicken, but the hoatzin is the only one where they can easily be observed and are actively used by the chicks to clamber around trees.

Hoatzin’s have further been found to be the only ruminating birds, meaning that like cows or goats, they can effectively digest plant matter, a process which is achieved through a bacterial process occurring in the enlarged esophagus and crop of the bird. The fermentation process can take the hoatzin up to 45 hours, a digestion period during which they are not particularly active or enthusiastic to move, and making their lifestyle somewhat slow and lethargic. Fermenting leaf and grass matter in this way also produces an abominable cloud of smell around these birds, earning this poor bird the unflattering nickname “stinkbird”.

The sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus)

Sacred Ibises are widespread, wetland dwelling birds, being found around Africa and the middle east. It’s biggest claim to fame is it’s association with the Egyptian god Thoth, god of wisdom, science, art and death, as a result of which, the sacred ibis has often been found mummified alongside pharaohs.

Flocks of this migrating bird will travel across the equator to benefit from the rainy season in the different hemispheres. When flying, like other ibises, these birds wil form a well coordinated v shape that has been found to significantly reduce each bird’s flying effort, as they time their wing flaps immaculately to surf on the air currents created by the other individuals.

Unlike other ibises, onomatopoeticly called “Hadedas”, who are known for their early morning concerts, the sacred ibis is of a more dignified and quiet sort. This dignity, however, does not prevent them from frequenting rubbish dumps in time of food scarcity like its Australian “bin chicken” cousins. Unfortunately this type of scavenging behavior can be very damaging to the birds due to increases of ingestion of plastic and other toxins, but it is becming more frequent across many bird species as wetlands and riverbanks are industrialised and the amphibians and other small aquatic creatures they feed on are becoming scarcer.

The ostrich (Struthio camelus)

Ostriches are phenomenal in every way: they are the largest birds by far, the fastest birds on land giving and at their peak performance even faster than horses with average sprinting speeds of 72 km/h but bursts of speeds up to 96 km/h. They are the only bird that is ridden and raced with jockeys (although this is not recommendable or especially ethical). They are farmed on industrial scales for their meat, leather and feathers, the latter of which has been a desired piece of jewelry, decoration or ritualistic object since the Egyptian dynasties.

Similar to other birds, mating in ostriches follows explicit and respected rituals and traditions, with the two sexes following ancestral dance routines and gestures. The ostrich further has an unusual breeding system, that is quite unique among birds. Eggs are incubated in communal nests, where they are cared for by a dominant couple- but many other females, who have either mated with the dominant male, or even females who have mated with another male and have been abandoned, will all lay their eggs in this communal nest – and then get up, never to be seen again. It is then up to the dominant couple to incubate and raise all the eggs. This requires a lot of work, since ostrich eggs- the largest eggs in the world- are highly desired sources of protein for many animals. Further the intense African sun and no protection, means that the eggs have to be regularly turned and moved to make sure they mature evenly. Meticulous turning can even ensure that all eggs hatch at around the same time even if they were laid many days apart. Incubation duties are split, the female staying by the nest in the day and the male in the night- their plumage is a perfect adaptation to this, as the female’s grey- brown coat camouflages her against the dirt in the day, and the male’s black feathers make him fade into the night.

The shoebill (Balaeniceps rex)

This must be another one of my favourite birds. The prehistoric, but always in fashion, shoebill. Due to their quite exotic look they have been shuffled between orders, however recent genetic evidence suggests them to be in the same order as pelicans. Found in the murky swamps and marshes of the heart of darkness in central Africa, they were only described in European literature in the mid eighteen hundreds.

They are a picture of patience. Ambush predators, they remain motionless above the water in wait of unsuspecting fish to appear near the surface with some of their favourites being bichirs and lungfish. While their beak may appear like an old dutch wooden shoe, it is a vicious weapon, with a sharp hook at the tip and razor sharp edges around its sides, enough to pierce, hook and slice its prey. They are extremely solitary with home territories being far from each other and borders vigorously maintained. Although they form monogamous pairs they make sure to respect each others personal space as much as possible by spreading to opposite ends of their territory for as long as possible.

The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos)

Golden eagles are the most widespread species of eagles, found across the northern hemisphere. They are huge and powerful eagles with wingspans of around 1.5 metres and massive talons. They are the birds with the largest home range, maintaining territories of up to 200 square kilometres as their exclusive hunting ground. When patrolling the edges of their territories they will have exceptional fights with intruders, consisting of aerial displays of power through flight manouvres, but which can escalate to talon-locked- tumbling–from-the-sky kind of encounters.

This is a bird who has a long history with humans. Especially in Altai Mountain Mongol tradition, there exists an intimate bond with certain tribes that goes long past the age of Ghengis Khan. Since that time, eagle hunters start to train at the tender age of 13 years and will climb rock cliffs to capture a young bird when they are around 4 years old. Since females are larger and appear to respond to humans better, hunters will pick a baby girl. A long training and trust building period ensues, at the end of which the eagle will be riding along with the hunte, wearing a hatty kind of cap. When she picks up on the sounds or sights of an animal in the wintery mountains she will advise him before taking off to capture the prey and bring it back to him to share the loot. Due to their huge size, these eagles are able to capture prey as large as wolves. Although the eagles can live past 30 years, the hunter tradition maintains that any bird must be released after 10 years of living with the tribes to let it live out the last part of its life in the wild. In the past, the relationships with the eagles was an essential way for communities in the barren lands to get through winter, but these days it has become more of a sport in most parts of the world.

The chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus)

I think we sometimes forget how utterly splendid the common chicken is. For a bird that is among the most numerous vertebrates on earth (counting more than 23 billion and exponentially increasing) the average city dweller knows little of their nature, behavior, beauty or intelligence. Related closely to the pheasants, guinea fowl and partridges, the males especially have splendid feathers in iridescent colours around their neck and in their voluptuous tail.

For the upper echelons of chicken life there are numerous beauty pageants across the world that assess the plumage, body form and other characteristics of highly bred chicken. The common chicken has further been found to be quite intelligent, from being able to do simple math to navigating complex pecking orders in the flocks that they live in. Their social life has further made them empathetic and caring towards their young and friends (although they can be proper bitches to each other as well).

While they are on all accounts no less worthy of life than other birds, or other living beings for that matter, for the overwhelming percentage of chicken, life is hell on earth, and I don’t think there is another single species abused so viciously and on as large a scale by humans.